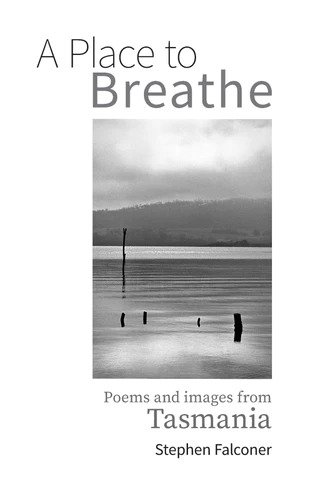

A Place to Breathe, by Stephen Falconer, Forty South Publishing, ISBN: 9780645736748, Fortysouth.com.au

Direct link to purchase: https://shop.fortysouth.com.au/products/a-place-to-breathe-poems-and-images-from-tasmania-by-stephen-falconer-pb

Apart from “Hope” (p. 198), each poem in A Place to Breath is attached to a location—from Falconer’s home country of Tasmania—in the table of contents and at the bottom of each poem. On many occasions, I read the title and stanzas and went back through the poem after gaining a new perspective from lines like “Paper Mill, Boyer” and “Fingal Primary School” at the bottom of the page. Even as these spaces were described line by line, I often revealed something from reading listed locations that accompany Falconer’s descriptions of his environment and observations on love, mortality, serenity, and other weighty emotions. There is something about the many places within Tasmania and Falconer’s relationship to them that allow engagement with these easily obscured pieces of our mind.

The intention of including location seems to vary by poem. Some serve as backdrops to Falconer’s thoughts; others take a step further and turn the poem on its head to evoke new meaning. Take this excerpt from the first poem, “Significant Other” (p. 1–2), which is followed by the location:

Listened to my heart,

imagined the beat of greater being,

who turned flesh into movement, blood

the same hue suffusing the sunset,

breathing the rise

and fall of moon and ragged cloud,

high mountain and deepest valley

Unmarked Graves, Wybalenna, Flinders Island

The location speaks for a writer as the writer speaks for himself. The solemn quality of an unmarked grave noticeably interacts with Falconer’s emotions and thoughts as they mix with concepts of the physical world, human bodies, and spirituality.

Although my home is far from Tasmania, I share much of Falconer’s nostalgia for his homeland. Perhaps we all know the comfort of those little things that make our homes feel like they do. The dilapidated church pictured in “Unattended” (p. 27), the cozy hotel “from a Dickens’s novel” in “Bonhomie” (p.185), or the defiance of a steam train in the twenty-first century in “Full Steam Ahead” (p. 134–5). All are in Tasmania, but could easily make up a few of the many out-of-time spaces across the United States. I felt a solid sense of familiarity with the wetlands of Legana, the designated location for “Artist” (p. 62–4), a section of which I am including below:

It’s so easy to disturb the wildlife,

to disrupt the patterns

of endeavor

where no one really belongs—

water levels that rise

and swamp foundations, mud thick

as bad blood between enemies

nevertheless, our intention demands participation

The well-written wetland imagery comforts me and provokes many memories of the abundant swamps in my hometown in Southern Maryland. My memory and nostalgia contrast with Falconer, whose thoughts on human interaction with a wetland as a framing device build on my view of nature’s fragility and my relationship with it. It proves Falconer’s ability to perceive well-known elements of our physical world and challenge the reader’s perspective with imagery and characterization that is simultaneously abstract and grounded.

Pieces of A Place to Breathe unearth Falconer’s nuanced view on the dichotomy between humans and nature. Poems like “Karma” (p. 12–13) acknowledge the unnecessary and harmful ways we waste our world’s gifts., and the collection’s introduction credits Tasmania’s beauty to the feeling that it “has yet to be totally overcome by the forces of economy and industry” (p. vii). Despite this, Falconer acknowledges that our built environment has its virtues. A picture in “Free Space” (p. 38–9) shows the side of a house and its doorway. The poem points out what makes the cozy but non-fancy atmosphere, including a leaning sapling that isn’t “determined to follow a graceful pattern” or the lanterns above the doorway that are hung “without need for brilliance.” As the title states, the water tower in “A Vital Function” (p. 90–1) shows that “even the least complicated material fabrication has beauty.” “Looking Forward” (p. 158–9) uses an old—and what looks to be abandoned from the accompanying picture—lime kiln in Eugenana to reflect on the human tendency to attempt to “create for a better world” despite our insignificance.

Falconer’s introspective, environmentally observant abilities come through each page of A Place to Breathe and demonstrate his ability to find peace and tranquility across diverse and sparsely-populated Tasmania. Even poems that take on darker, more traditionally negative topics and themes are approached with an accepting and contemplative mind state. “Natural Healing” (p. 170–2) touches on the phenomenon of depression with an unclear cause and the additional anxieties provoked by its mysterious nature. The final lines give hopeful insight, perhaps to those who also struggle:

But when we stand at the edge

of another hole,

a black-green depression,

in an exclamation

of wonder,

imagine

a deeper source

at the centre

Sinkhole, Tarkine

Amongst all the recognition of nature’s elegance, the last stanza of “Heatwave” (p. 112) acknowledges its apathy and tendency to inflict suffering. Previously occurring words in the poem, like “calm” and “dreamy,” are contrasted with the image of a lamb that has succumbed to the unforgiving heat and lies near its mother. The distinct, striking, and disturbing juxtapositions in “Equality” (p. 144–5) are puzzling yet ripe for interpretation. The surprise comes from the material in parentheses. It breaks up the relaxing and thoughtful prose with a darker voice that swears and conjures unsettling images of “rust flecked snow” and a “finger caught in the grindstone.”

The breadth of Falconer’s diction is impressive, and does good work to make the over 120 poems feel fresh and unique. As a side note, I would suggest that readers keep a pocket dictionary on their person. While “felicitous,” “piquancy,” and “effervescent” in “Merry” (p. 58–9) sent me on a detour to Merriam-Webster, I found that they contributed to the rich atmosphere that the poem cultivates. If you are looking for a contemplative and (mostly) comforting collection of poems that makes you feel at home and in a faraway land, A Place to Breath fills that niche with great variety.

Favorite Poems: “Equality,” “A Bright New Day,” “Free Space.”© Stephen Falconer and Michael Fialkowski

Stephen Falconer is an Australian poet who lives with his wife, Helen, in Latrobe, Tasmania. Apart from two collections published by Wipfandstock, Oregon- “‘Indebted to Change’ and ‘Arcadian Grace’, he is currently finishing off a work exploring mystical traditions poetically.

Michael Fialkowski is the Social Media Editor of Loch Raven Review. He graduated University of Maryland, Baltimore County with a communications degree and a creative writing minor. He lives in Washington, DC, and is a content editor and certification associate at the National Association of Housing and Redevelopment Officials.