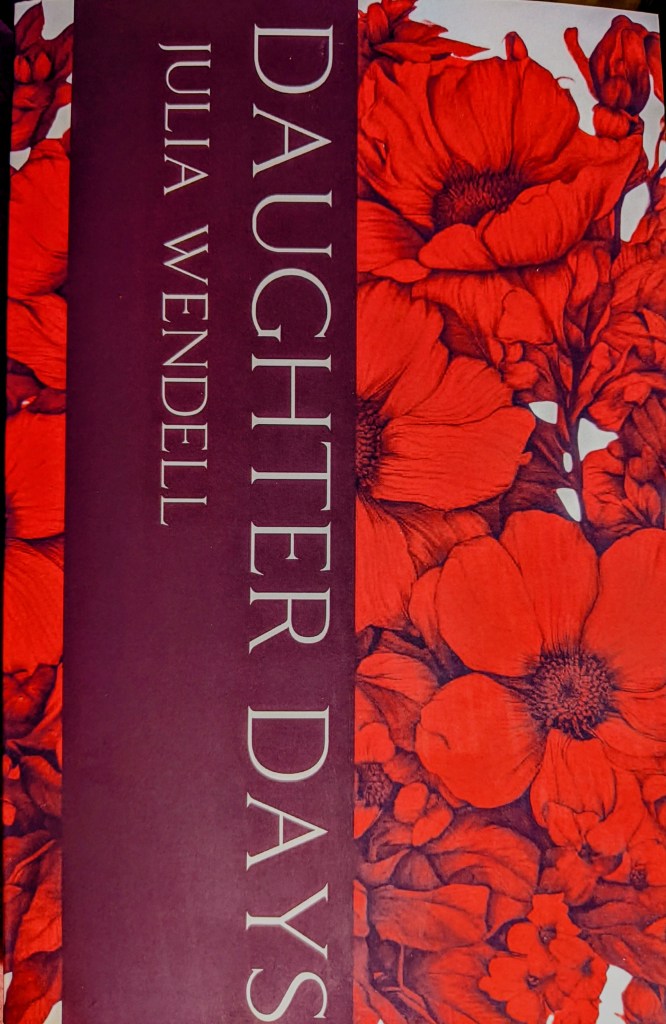

Juliai Wendell, Daughter Days, Unsolicited Press, Portland, OR, 2025, 132 pages, ISBN 978-1-963115-34-5, $18.95

Drawing on many decades and multiple generations, Julia Wendell’s Daughter Days includes daughters growing into women, women into mothers, and women choosing not to be mothers. One of these women is visited by “children I have chosen not to have.” Wendell takes us through the loss of a marriage, the cyclical nature of life, raising children, wishing those children happy even when they believe you don’t, echoes through generations, life and …not life. We begin with a teen whose

…worry turns to relief turns

to the beginning of a future

of the always encroaching.

“What would I have you take back?” asks an older speaker looking back to when she discovered her period started. The event typically so yearned for in a girl’s life, that possibility of having more than one life inside your singular body.

In “Choice,” a young woman entering a clinic pledges

In another life

I’ll spoon for you sliced peaches

from a stainless cup.

I’ll plait violets

into your chestnut hair.

The specificity and tender detail, especially at the beginning of the poem, suggest the speaker’s internal conflict. She desires children – but not now. Toward the end of the poem, there are many images of fragility, perhaps reflecting the feelings of the speaker and the reality of the fetus:

…membrane of glass.

Tadpole, unfinished thought

that went astray, you’re nothing.

They say the heart is beating now,

but it’s so small I can’t hear it.

You’re a mistake the hollow in me made,

you’re my belly swelling with doubt.

A heart so small it’s impossible to hear. A mistake, an unfinished thought, you’re nothing. Is the speaker trying to convince herself? Or is she revealing the hard truth that in order for some to live, some must die – as simple as the food chain we find in a gorgeous poem later in the book, “Owl.”

In the final stanza of “Choice”

…through the clinic doors,

parting as if by magic

making everything that just happened

disappear.

A single word – the final line, the young woman alone in her body again. While the speaker may be physically returned to herself, she is not free of that life she was not ready for. The unborn remain with her as spirits or ghosts and reappear in this powerful, moving collection.

“Tilling the Grave” is filled with physical movement: “…loosen the earth…, he tills and tills, …digs some more, …trudges through.” All this before:

He drives off to collect her

from the vet’s freezer,

then instructs his wife to keep the children inside

until he can get her just right.

He drags the stiffened animal

across the lawn on a tarp…

The father arranges the large dog in the hole he has dug in the frozen earth,

“… and a bone goes in beside her.” Then we see “… my 5-year-old son’s chest heaving,” each child lowered “into the earth in turn to touch the dog” followed by the work of “pushing clay and loam onto the matted fur.”

Every parent who has also had pets knows the difficulty of what Wendell expressess in so few words: “… and a bone goes in beside her.”

That detail breaks my heart. It is so simple yet says so much about our culture’s inability to deal with death, especially when we try to teach our children about it. We don’t want to admit that, as far as we know, death is no more than the cold earth and decomposition. We have to include the possibility of pleasure, familiarity, comfort, to ease the finality of death for them, for ourselves. The poem is so spare, focused on the physical work of this funeral scene, but it cuts deep.

“In the Pasture of Dead Horses” we have a poem that includes extended family and experiences that echo through time. An experienced horsewoman herself, Wendell watches children:

…repeat themselves on the backs of saddled ponies

circling a weather-worn ring

north of Baltimore.

…Before my mother,

ambushed by marriage and childbirth, left, too,

then returned to the house of her childhood.

Fifty years of opening the same windows

to the usual shadows and drafts.

Daylight struck over and over…

Dear God, yes! “Ambushed by marriage and childbirth” may be my favorite phrase in the book. While the poem perhaps speaks of men marrying quickly before going to war, this phrase applies to far too many women who aren’t military wives.

We are repeated

on the backs of saddled ponies–

my mother, my children, and I

…a young woman revised

in the clunky staccato of small hooves

wearing circles in a ring,

each circuit ending

and ending again.

Simple language used beautifully to create layers of sound and meaning!

The exquisite poem “Owl,” begins with a child saying “Bird,” an adult specifying “Owl.” The next day, “Mouse” becomes “Breakfast.” And the speaker goes on:

I am not above revealing

cycles of violent need

to even the smallest person.

It will eventually make sense.

The girl will grow up

and learn to kill and kill and kill–

bugs, engines, books, time, love…

Owl, says the budding girl.

Life, says the old one, me.

Here’s our speaker, ready and willing to share the hard realities of life with “even the smallest person.” Counting on their growing up, on reality maintaining its insistence that some must die, on that becoming everyone’s everyday reality. While I have no evidence to the contrary, and current events don’t suggest much help is coming, something in me wants to resist. Being realistic has never been a particular strength of mine.

The continuity of emotion is smoothly maintained through this intimate mix of memoir and poetry. It includes life’s messy, uncomfortable moments (death of the family pet, divorce, constructing blended families, continuing to love a child who believes you never have and never will) as well as attempts to celebrate each member’s successes.

While most of the poems address challenging or difficult situations, I would not call Daughter Days dark because there is acceptance of the past and movement toward the future including the love and good wishes most parents feel for their children. Wendell’s words move us forward; her excellent, spare use of language and detail convey deep truths. She does not pretend to have no flaws – another poem I’d love to discuss relates to our inability to hide our weaknesses from our children. She collects it all: shiny or bloody, perfect or sweaty, Wendell weaves it together beautifully.

If you are a mother, sister, aunt, daughter, or if you love one, Daughter Days would make the perfect Mother’s Day gift.

© Julia Wendell and Virginia Crawford

Julia Wendell’s sixth collection of poems, The Art of Falling, was published by FutureCycle Press in 2022. A Puschcart winner and recipient of Fellowships from Breadloaf and Yaddo, her poems have appeared widely in magazines such as American Poetry Review, Missouri Review, Prairie Schooner, Cimarron Review, and Nimrod. She is the Founding Editor of Galileo Press, lives in Aiken, South Carolina, and is a three-day event rider.

Virginia Crawford, a Baltimore native, earned a BFA in creative writing from Emerson College, Bolston, and a Master’s of Letters from the University of St. Andrews, Scotland. She has published individual poems in such journals as Gargoyle, has taught as a Maryland State Arts Council’s Artists in Education for more than twenty years, and is married to fellow-poet Sam Schmidt. They can be found at Married Poets, https://www.patreon.com/c/SamandVirginia?redirect=true, and her books include Touch, 2013, and questions for water, 2021.